The Look of the Bible: Genres, Part 1

This is the first part of a series of reflections on the various “genres” of Bible design. In this installment, we'll look at the classics, the formats that were developed, perfected, imitated, and eventually handed down to us in the late twentieth century, when I started thinking about the Bible as a design challenge.

Some stories delight us by embodying their genre, while others impress by bending or even subverting our expectations. A good detective story, for example, can tick every box in the formula without coming off as formulaic, or it can dispense with the conventions entirely and satisfy through surprise. There are readers who want the rules to be followed scrupulously and others who desire anything but that—but for most of us the deciding factor is not the rules themselves but what the storyteller makes of them.

Bible design has its genres, too, and they function in similar ways. A good design might adhere to the conventions; then again, it may defy them, and in the process perhaps even redefine them. Given the variety of editions on the shelves these days, I think it helps to have a grasp of the many genres of Bible design, the ones that have been handed down to us as well as the new ones that are emerging in our unexpected golden age.

Sadly, I am not much of a systematician. I’m incapable of giving you an exhaustive list, and uninterested in trying. But let’s consider some of the obvious examples.

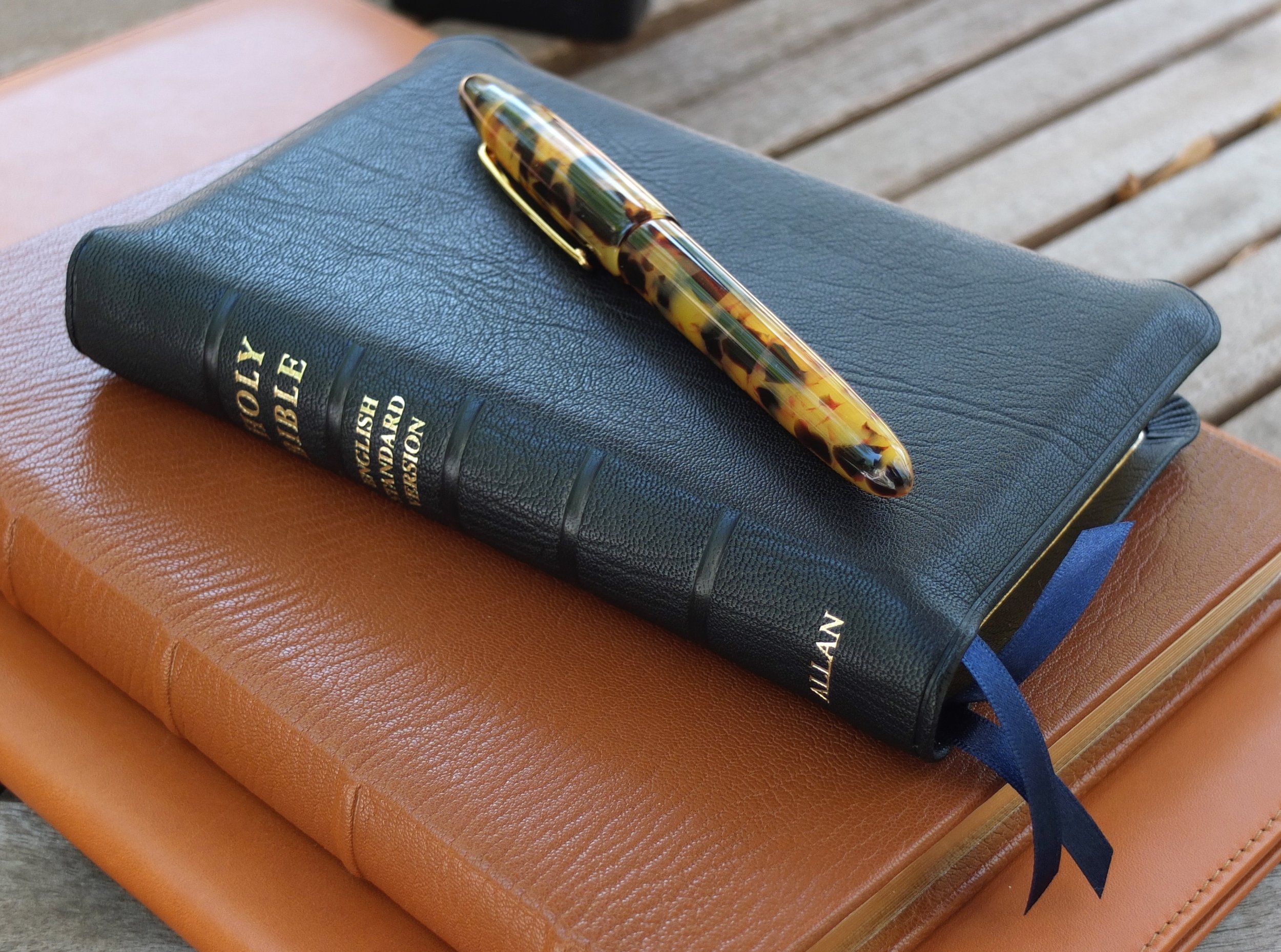

The Reference Bible is the cornerstone of classic design, the default standard people my age associate with the Scriptures in print. In the traditional iteration, a Reference Bible coupled the biblical text (set in two columns) with an additional column of cross-references. Chapter and verse divisions were prominent, and section titles might appear in a running header or inside the text itself. Concordances and other helps would be tucked in back of the book. The goal of the reference apparatus was to help the reader find particular passages efficiently and discover parallels that could shed light on the meaning.

The Wide Margin Bible was essentially a variation on the theme, a Reference Bible printed with additional room around the edges for note taking. You could argue that Wide Margin Bibles were not a separate genre at all, since you could create one by simply enlarging the size of the page — just as you could create a “compact” edition by reducing the scale of the same layout, or a “thinline” by juking the proportions and paper to make the same layout feel slimmer in the hand. But genre distinctions are porous in design, just as they are in storytelling. For me, a Wide Margin Bible (and for that matter a Compact, or a Thinline) felt like its own thing.

The Study Bible was another iteration of the Reference, though I suppose it borrowed from the Wide Margin, too. Instead blank space for your own notes, it came with scholarly annotations that took you much deeper into the context, meaning, and possible interpretations of the text. The trade-off, of course, is that as the notes became more comprehensive there was less room on the page for the text of Scripture. The original Geneva Bible resembled a Reference Bible whose margins were packed with minuscule type, essentially a ‘pre-annotated’ Wide Margin, while the Study Bibles of my youth had a lot more annotation than Scripture on each spread. In fact, the scriptural text sometimes appeared to have be de-emphasized in relation to the notes.

Let's stop there for a moment. When I began to write about Bible design twenty years ago, Reference Bibles were the norm, Wide Margins were fading away, and Study Bibles were making huge strides. If you were serious about Scripture, you probably carried a Study Bible to church. If you were serious and enough of a pedant you lectured people about using a Wide Margin to create a Study Bible of your own and lamented how hard it was getting to find a good one — guilty as charged!

From the start, I had a problem with the genres we’d inherited.

Actually, that’s not quite right. It wasn't the genres themselves so much as the way they were being perpetuated. It seemed to me that Bibles were being designed without a lot of thought, that the rules were being followed simply because they were the rules. We were no longer aware that design choices were being made. Instead, Bibles looked the way they looked for the same reason churches ran the programs they ran: because that’s what everyone else is doing. We were not thinking about the way the classic forms might be influenced how we read the Bible, or misread it.

I had a hunch that the way we designed Bibles could be just as important to their interpretation as the way we translated them. But I’ll pick up that thread in the next installment of the series: “Reformation or Revolution: Genres, Part 2.”